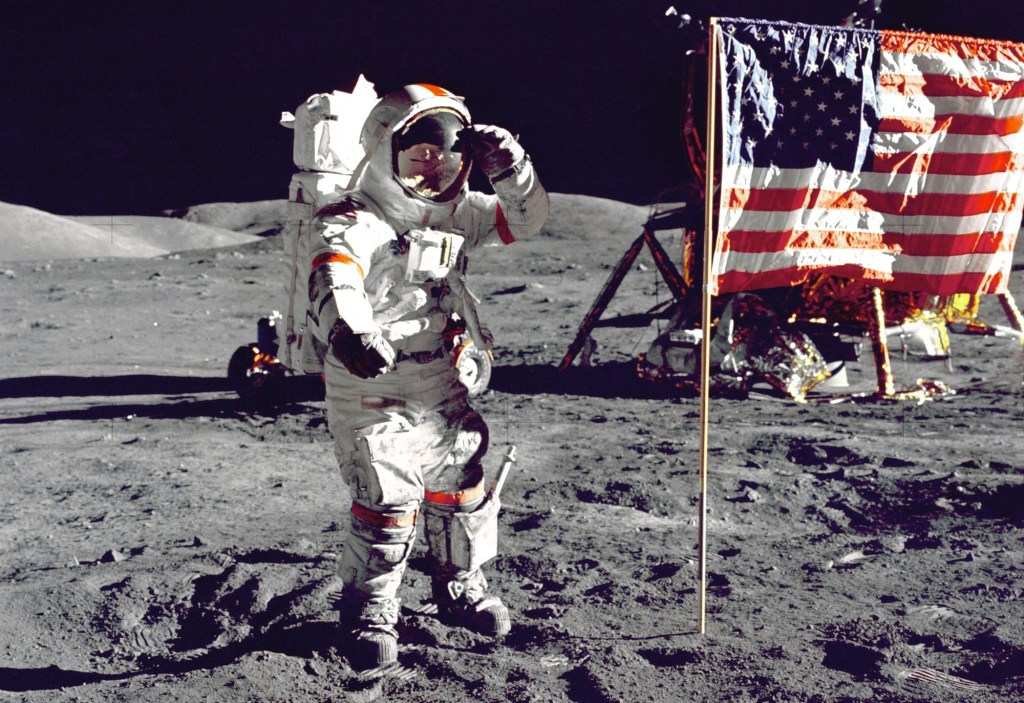

The strategies NASA employed to reach the moon in the 1960s can still inform space and other technology leaders today on how to pursue big goals and recover from inevitable setbacks. | Michel Euler/AP Photo

This July 20 marks 50 years since one of mankind’s greatest triumphs — when the first humans reached the surface of the moon.

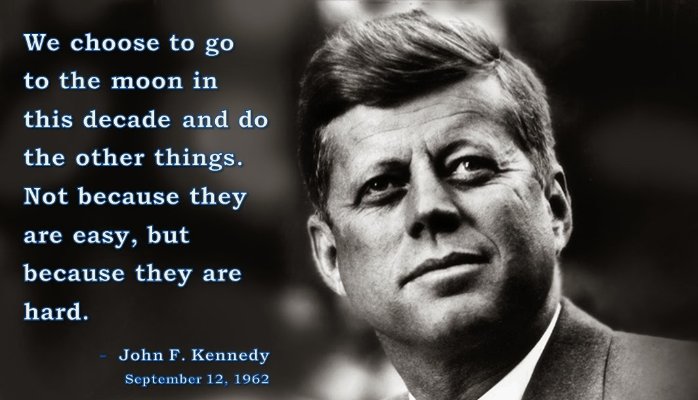

The historic Apollo 11 mission was culmination of the work of a relatively small group of leaders at NASA who marshaled private firms, government and academic partners, and public goodwill to achieve the bold vision laid out by of President John F. Kennedy in less than a decade.

NASA faced a host of challenges — politically, technologically, and financially — as it sought to reach the moon in the 1960s. The strategies it employed can still inform space and other technology leaders today on how to pursue big goals and recover from the inevitable setbacks:

What’s your moon shot”? When President Kennedy set America on the course to the moon he sought a game-changing goal. Why? Because we were seemingly losing to the Russians in space and in the international political arena. To change the game, JFK changed the goal – to one that at the time seemed impossible. In today’s tech industry parlance, a “moon shot” is a “BHAG,” or a Big Hairy Audacious Goal. Putting a BHAG out there is a way to truly propel a business past its own perceived limitations and eventually the competition. But as businesses grow they can get more conservative. To stay on top they need to another a “moon shot” in the distance.

Collaboration is king. Large goals live and die by collaboration. If a leader shows he or she is collaborating, their subordinates will want to demonstrate their own collaborative work ethic. Kennedy’s NASA administrator, James Webb, modeled this when he instituted “The Triad,” a three-person team that made all of NASA’s biggest decisions collectively. Webb also stood out for his efforts to break down silos within NASA and his ability to get research, engineering, purchasing, manufacturing and operations to communicate and work together to achieve goals.

Some of your best allies are on the outside. NASA’s success was also the product of the many alliances it formed with disparate academic and research institutions, not-for-profits, elected leaders and other politically powerful players. When a big task was at hand, NASA often looked for resources outside the organization to get the job done. For instance, to solve the issue of overheating upon re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere at 26,000 mph, NASA worked with MIT, Corning Glass, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and others to create a shield that could withstand 3,000 degrees to safeguard the astronauts.

Know what’s going down. For businesses to succeed, their leaders must understand the larger ecosystem in which they operate. As the Apollo program got underway, the civil rights movement and a more politically active youth culture were coming to the fore in America. The leadership of the Apollo program responded by putting an emphasis on bringing in more minorities, women and young people. The median age of the staff working in Mission Control during the Apollo 11 moon landing was 24!

Be ready for a major about face . Sometimes businesses get stuck in the mission and are resistant to strategic changes. For NASA in the 1960s, it was all about beating the Soviet Union to the moon. But fast forward to 1972 and we were laterally shaking hands with Russian cosmonauts in space. The joint Apollo/Soyuz mission was the culmination of a pivot from competition to cooperation. Organizations that hold on too tightly to their original sense of competition can ultimately lose the race.

Assume failure. NASA’s Apollo program was almost decimated before it started. After the successes of the Mercury and Gemini programs we were over confident in our success. Then three astronauts died in the Apollo 1 fire. It set NASA and the nation back. Another crew was almost lost in space during the Apollo 13 mission. In each case NASA’s leaders were prepared to lead their organizations out of the ditch by being forthcoming about the causes of the setbacks. NASA invited third-party experts to help determine the shortcomings and create solutions — and was very public about it all.

And beware of hubris. In the aftermath of the Apollo 1 tragedy, NASA was very up front about one huge failing: that its previous successes led to a sense of invincibility. NASA had considered remedying what proved to be a contributing factor in the deadly fire — the pure oxygen atmosphere in the space capsule — but chose not to adddress it because it hadn’t been an issue before. When success comes, pat yourself on the back once and keep the celebration short. There’s always another moon shot to aim for on your horizon.

Dick Richardson is the founder and CEO of Experience to Lead, a firm that offers immersive experiences to improve the leadership skills of senior business executives. He is also the author of the book “Apollo Leadership Lessons.”

Original article found at https://www.politico.com/story/2019/07/19/7-lessons-from-the-moon-landing-1416542